Oral language skills are vitally important for your students to master—both for social and academic success. Learners use this skill throughout the day to process and deliver instructions, make requests, ask questions, receive new information, and interact with peers.

As a teacher, there’s a lot you can do during your everyday lessons to support the development of strong oral language skills in your students. Today’s post, excerpted and adapted from Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, OWL LD, and Dyscalculia , by Berninger & Wolf, gives you 14 ideas for supporting oral language development in your students who are verbal. These teaching strategies can help students with specific language disabilities (including dyslexia), and they can boost the language skills of your other learners, too. Try these and see which ones work best for your students!

Identify an individual student’s profile of strengths and weaknesses in oral and written language early in the school year so you can plan and implement differentiated instruction as needed. (Use the reliable TILLS assessment to get a complete picture of both oral and written language, with an innovative framework that shows how these skills relate to each other.)

Every social interaction gives students a new opportunity to practice language. Some of your students might need a little guidance from you to engage in conversations, so spark interactions whenever you can. Ask questions, rephrase the student’s answers, and give prompts that encourage oral conversations to continue.

Your students may not use complete oral syntax in informal speech, but encourage them to do so when they’re in the classroom. When a student uses fragmented syntax, model complete syntax back to them. This builds oral language skills and gives students practice in a skill necessary for mastering written language.

Engage in eye contact with students during instruction and encourage them to do the same. Maintaining eye contact will help learners gauge their audience’s attention and adjust their language, their volume, or the organization of their speech. This will help them be better understood, communicate more clearly, and successfully interpret nonverbal cues about their clarity.

Students are expected to understand the need for capitalizing the beginning of a sentence and placing a period or other punctuation at the end. This expectation assumes that students always recognize sentences, even though we do not always speak in complete sentences. By Grade 4, students should reliably write in complete sentences. Being able to organize and express answers clearly first in oral language is a foundation for later writing of organized, clear sentences.

Ask students to feel the muscles used for speech while they’re talking and monitor their volume and articulation. Remind them that clear and loud-enough speech is essential for holding the attention of the group and communicating their information and opinions effectively.

Encourage students to verbally summarize or otherwise discuss the information they hear. This should begin in kindergarten and continue with increasingly difficult questions as students grow older. Teach students to ask for clarification when they don’t understand something, and emphasize that they can ask you directly or query fellow students.

Introducing students to concepts such as nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives will allow the class to understand and answer the comprehension questions they encounter as they read text. Throughout the year, read and discuss children’s books, which are written in a lively, engaging way for developing language learners. Some are explicitly written toward the goal of teaching different parts of speech that students can identify within their own oral and written language use.

Some students have trouble getting started with the wording of a sentence. Saying the beginning word or phrase for the student can help the student structure their response. Give students time for thinking and formulating an oral or written response. Students’ explicit experience in both producing their own oral language and processing others’ language will help facilitate their comprehension of reading material.

Your students have probably experienced playground arguments related to tone; misunderstandings are common when students are using loud outdoor voices. Remind your students how tone of voice—which includes pitch, volume, speed, and rhythm—can change the meaning of what a speaker says. Often, it’s not what they say, it’s how they say it that can lead to misunderstanding of motives and attitudes. Ask your students to be mindful of tone when they’re trying to get a message across, and adjust their volume and pitch accordingly.

Ensure that your students are listening by using consistent cues to get their attention. You might use a phrase like “It’s listening time” to give students a reminder. Some students might also benefit from written reminders posted prominently on your wall.

During each school day’s opening activities, ask a question to encourage talk. (You can even write one on the board so your students can read it and start thinking about their answer as soon as they come in.) Start with simple one-part questions like “What is your favorite animal?” If a student doesn’t answer in a complete sentence, model a complete sentence and ask the student to repeat your model. Once your students are successfully answering these simple questions in complete sentences, move to two-part questions that require more complex answers: “What is your favorite animal? Why?”

Give your students a sentence to finish, such as “When my dog got lost I looked…” Have each student contribute a prepositional phrase to complete the sentence (e.g., at the grocery store, in the park, under the bed). Then have your students create a class booklet by writing and illustrating their phrases. When all the phrase pages are assembled into a booklet, students can practice reading the very long sentence with all the places they looked for the dog. Encourage them to come up with a conclusion to the story.

Some students may have difficulty with abstract concepts such as before, after, or following, and with sequences such as days of the week or months of the year. To help students learn and retain these concepts, you may need to present and review them many times and in multiple ways. For example:

Asking questions before and after a reading assignment not only helps sharpen oral language skills, it also helps students think about what they’re reading and absorb information from the words. You might try the following strategies to facilitate reading comprehension:

Oral reading fluency refers to how rapidly, smoothly, effortlessly, and automatically students read text. The goal is accurate and fluid reading with adequate speed, appropriate phrasing, and correct intonation. Here are a few activities that aid fluency:

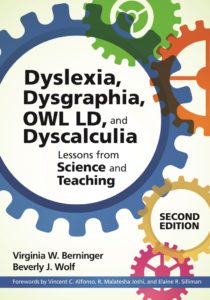

You use oral language every day to teach—but some students may not be getting your message. In this chart from Berninger & Wolf’s book, Beverly Wolf shares some examples of how students in her classroom misinterpreted sentences delivered orally:

Be aware of the potential disconnect between what you say and what your students hear. Go over your message and present it in multiple ways to be sure all students understand.

Oral language is one of the foundational building blocks of learning. Try the suggestions in today’s post to give students the oral language skills they need for future academic and social success, and check out the resources below for more on screening and teaching language skills.

Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, OWL LD, and Dyscalculia

By Virginia W. Berninger, Ph.D., & Beverly J. Wolf, M.Ed.

Learn how to provide effective instruction for students with learning disabilities while meeting the needs of all students! This teacher training text prepares educators to deliver explicit and engaging instruction customized to the needs of their students. Critical insights from diverse fields blend with lessons learned from teaching experience.

Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills, Fourth Edition

Edited by Judith R. Birsh, Ed.D., CALT-QI, & Suzanne Carreker, Ph.D., CALT-QI

The most comprehensive text on multisensory teaching, this book prepares educators to use specific evidence-based approaches that improve struggling students’ language skills and academic outcomes in elementary through high school.

45 Strategies That Support Young Dual Language Learners

By Shauna L. Tominey, Ph.D., & Elisabeth C. O’Bryon, Ph.D., NCSP

Discover 45 of today’s best strategies for teaching young dual language learners and supporting their families. Includes practical guidance on how to apply each strategy in real-world classrooms!

Quick Interactive Language Screener™ (QUILS™)

A Measure of Vocabulary, Syntax, and Language Acquisition Skills in Young Children

By Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, Ph.D., Jill de Villiers, Ph.D., Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek, Ph.D., Aquiles Iglesias, Ph.D., and Mary Sweig Wilson, Ph.D.

Early identification is the first step to helping children with language delays improve their skills. Find the children who might need help with QUILS, a one-of-a-kind tool that helps you evaluate whether children are making language progress appropriate for their age group.